Tiny rivulets of water coursed down the walls. It had rained the day before. And some days before then as well. It was March in Beirut after all. The season of rain. Even though it was cool outside I could feel the thick dampness around me. It sealed me in. I took a deep breath in the poorly lit room and could taste the acidic overtones of pulverized stone, old gunpowder and something worse.

Though the sun had broken out when I started earlier that morning I couldn’t quite tell what color the sky was from that barely held together chair in that basement. Hours had passed and no windows. It might be raining again. It might still be sunny. Time seemed to hang in the air as I pulled my breath in slowly trying to avoid the taste of it.

The hard light of the two bare bulbs hanging in that room made the droplets of water on the walls sparkle. I could focus just there. It helped me avoid the hard stares of my captors. Their grim faces contrasted the stained and yellowed photos on the walls. 11 of them smiling beatifically. Each photo seemed to have been purloined from the ID cards everyone carried even during the war. Those cards were essential to survival at times. They would identify your neighborhood and religion. Some could tell that with the way you answered a simple and innocuous question in arabic. “Excuse me but what time is it?” they would ask. Depending on your accent when you answered you might end up in the same chair as me or in an instant, much worse. Everyone looked for the differences. And many had been killed for them. Like the 11 photos in front of me. I’d learn later, much later, that they died as martyrs for the Virgin Mary. Perhaps because someone they knew had answered the question wrong.

Hours earlier a boy soldier dressed in oversized fatigues and a helmet that fit like a cartoon had stuck the killing end of his AK 47 into my chest and pushed me with the shove of the barrel down into this basement. I was 21 and an aspiring war photographer. He was probably just 16 and despite his new uniform, as I would learn later, had been carrying his AK since he was 11. The weapon showed the years. And his eyes showed the pain.

Ronald Reagan was president and was indifferent. The Marine barracks and French embassy had been bombed a few months before. After the bombings the Marines withdrew to the beaches. Better for a quick getaway. Sabra and Shatilla had happened a year earlier and the kidnappings of Americans had just begun. I was out during a cease-fire and the Lebanese were eternal optimists so maybe, I thought, all that was ending.

With cameras around my neck and a bag of lenses and film at my side I walked down the eight flights of stairs. Electricity in our building was intermittent which made for a climb when it went off but we all got used to it. When we moved into the apartment a few months earlier the furniture had to be carried up. No electricity that day. A sixty year old Kurd carried our refrigerator on his back with a strap across his forehead and a smile when he reached our doorstep. “We are mountain people”, he told us.

I left our building and walked down Hamra Street. Passing all the boutiques which always seemed to remain open no matter how many times they’d been bombed. If there was one thing the Lebanese desired above all others, it was a desire to be well dressed. The Armani store had been bombed eight times. And reopened eight times. Fashion was an emotional bulwark as their city and country crumbled violently around them.

Soon I started to walk through checkpoints manned by the militias. Most of them were smoking cigarettes and playing backgammon. Some of them leaned against their weapons and most ignored me as I walked by. A gunner on an APC swiveled his 50 cal into the wind tracking a bird. The camera gear offered me a sense of impunity and whether by my own attitude or the cameras around my neck I wasn’t stopped and kept walking.

I walked around the Green Line for a few hours and came across an old broken down weight bench in front of a mound of sandbags. My stroll until then was filled with silence. Not a person or an animal of any sort was around. Not even a bird in the sky. Till that moment I was left with my own thoughts walking down memories of an old Beirut I had loved. The click of the camera shutter was the only sound I had.

The weight bench was a strange sight, incongruous in the middle of a rubble strewn street. A towel was thrown over the bar. Obviously used though no one seemed to be around. I pointed my camera to see if my lens could help me make sense of the thing.

The boy soldier broke my reverie. He appeared from nowhere quickly. I heard the click of the safety lever going off. I was more than a foot taller than him. But he had the weapon. In each hand I raised my two cameras high in the air. My own personal white flags.

Those two cameras had been my passport. Until he asked for my press pass. I had none. And I knew immediately that I was in trouble when that answer got stuck in the back of my throat. I couldn’t talk at the business end of an AK. And I didn’t trust a teenager with a weapon bigger than him and his finger on the trigger.

With my hands overhead and my voice caught like a stone in my throat he turned me around and jammed his AK against my spine. This time with more force that hurt. I held the cameras higher as I desperately tried to find my voice. I had hoped that the altitude of those cameras would reveal the earnest supplicant I had suddenly become. If I didn’t have my voice I’d certainly have my reach.

He pushed me forward and I stumbled towards the stacked sand bags that hid an entrance. Those piles had been there a long time. Weeds had started to grow through them. My mind slowed and I wondered if the rain had helped those weeds grow. It’s strange what you notice when you’ve got a gun at your back and a dark bunker in front of you. There were bits of time that seemed to move in slow motion and more that moved way too fast. I hadn’t told anyone where I’d be off to that morning. I worried that no one would find me on the other side of that basement.

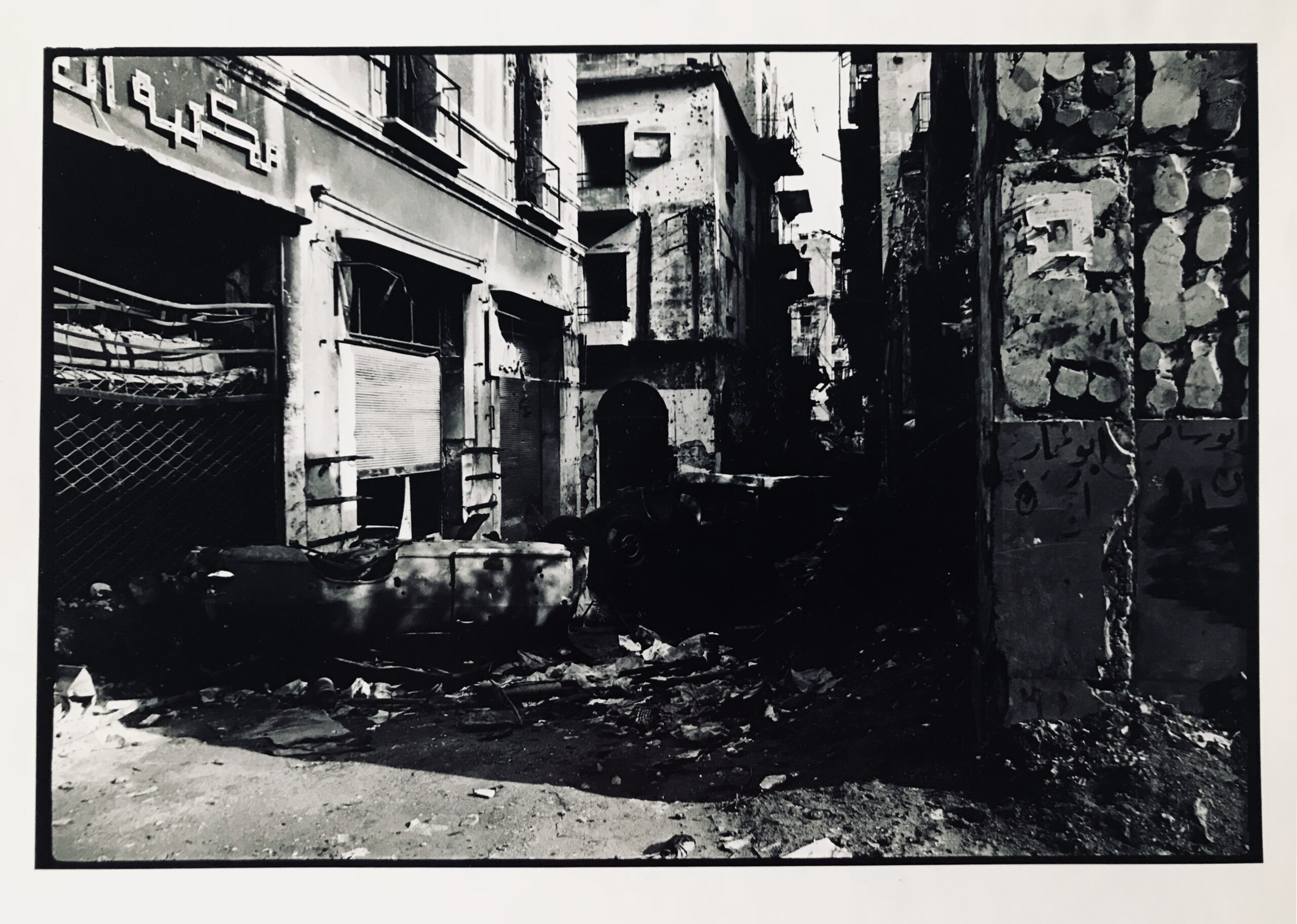

The day before the militias had called a cease-fire and I had decided that after the rain it would make for a good day to walk the Green Line. Green it was because after nearly ten years of fighting blocks and blocks of abandoned buildings and rubble had sprouted trees and weeds. The trees were small and scrawny. I’m sure they were being culled constantly by the incessant shelling and small arms fire. What was left of the buildings that still stood had been eroded by bullets, RPGs and shelling. As I walked I’d see single walls of buildings barely standing on their own accord. Absurdist nightmares of a neighborhood that was once the center of a beautiful city.

Some streets were stacked with husked out cars and rusted buses. From time to time an occasional well destroyed armored vehicle or a tank made the scene more interesting. Much of it was piled meters high. Roadblocks. The smell of it all was quite peculiar. The rain had freshened the air a bit. I could smell the earth and approaching spring. But in some places the smell was much stronger. Not garbage. Like dead chickens but much worse. Most of the time I stayed well away from the rubble that reeked. Often my walk was dead ended by signs warning about mines. Once I stopped and looked into a blasted out building that had been marked with skulls and saw at least a dozen or so anti-personnel mines scattered on the floor. I walked quickly on. Not because of the skulls or the mines but because of the smell.

At the base of roadblocks I’d find broken ampules of vitamin B and empty bottles of methamphetamines. Both were being used by the militias to keep awake and fighting. They were mixed in with seas of spent shell casings sprayed over the street like an orgasm of violence. Thousands and thousands of them. I could tell the recently spent ones by their still coppery brightness. Lots of those. The cease fire had been announced just yesterday and the coppery glisten was testimony to just the few hours that had passed since the cease-fire was agreed to.

After ten years of civil war the fighting had become very workmanlike. Cease-fires were well respected. Despite the optimism they’d usually last just a day or two. Just enough for the militias to take a break. Like a good long weekend. And then back to the fighting at hand.

I had grown up in Beirut and knew the Lebanese to be optimists. As I walked through the shattered city blocks I wondered if they had, despite the years of civil war, might have also called the Green Line green because it would signal a future more hopeful than their past. Or maybe they called it green because that was the place to go whenever you wanted to shoot at someone else. All fights are fair here. It’s the Green Line.

And fight across that green line they did. Brutally. Many many people had died. Many more across the country. And when the war ended some four years after I left the official record was 250,000. In a country of less than 3 million that official number made a difference. And we all knew the number was probably much higher. And made much more of a difference to the families who had been affected by the war.

It was a nasty fight. What had started as a conflict between the Palestinians and the Lebanese in the late 1970s had devolved into an internecine war where religious factions devolved further as time went on into open block by block gang warfare. Amidst the usual fighting kidnappings and drive by executions had seemed to be the order of the day. I saw photos of human ears strung together and worn as necklaces. And fingers. Talismans of the working militias.

The Israelis had come in 1982. I arrived with the International Red Cross still working and residing in our building. They’d been there since the Sabra and Shatila massacre. We were told by them that the Palestinians in those camps were murdered by “cold” weapons. Cold meant knives. 3500 children, women and old people had been slaughtered by cold weapons.

I had begun my walk that morning leaving the apartment building hoping to explore a neighborhood I once knew well. The Green Line separated the Christian East and the Moslem West parts of Beirut. It went block by destroyed block through the middle of Old Beirut. A place I had loved when I was a kid. It was where the best toy store was, where I got my made in England toy cars. I had the car from Man from Uncle. It was my prize possession. It was also where the best sweet shops were. And where all the small stores selling gold jewelry had been. The Old Souk. I’d walk by those stores with my mother. The jewelry glittered in her eyes. But that didn’t matter as much to me as the toy store. With my hands pressed against the glass, there I could dream. I found that store that morning. All destroyed and ground down. All that was left was a rusted sign.

All of it was rubble. The result of ten years of heavy fighting and more to come between heavily armed gangs. It was all a grudge match that started around the Crusades. The Middle East was like that. Nearly a thousand years of grudge matches started by someone far away banging on a minbar in a mosque or an altar in a church in the name of God calling for the death of someone else.

But that all escaped me in that basement. I was shoved into a chair in front of an old tired table that stood crookedly in the middle of the floor. It smelled of mold and dirt. When I was forced to sit I scanned the room quickly to see if I could tell where I was. There was a large pile of AKs and RPGs arranged neatly against the wall. The wall was spray painted with a crudely stenciled image of a tiger on top of the green cedar of the Lebanese flag. Ammo boxes stacked in corners and rockets for RPGs pushed against each other. Half empty jugs of water completed the decor. And I could make out a well used backgammon set. And the photos of the 11 martyrs.

It wasn’t just a basement. It was a completely fortified bunker, small and quite dark despite the two lightbulbs. I could sense the presence of others who moved in and out around me. There was tension and nervousness around. Easy to see and easier still to feel. Obviously the anxiety of waiting to fight even during a cease-fire. The boy soldier stood behind me with the barrel of his AK just a few inches from my head. I could feel it even though I didn’t dare to turn my head to look.

The chair across the table from me was quickly filled. Everything down there seem to happen very quickly. Between us was a single upright bullet placed carefully on the table. Half in fatigues and a t-shirt with a few nasty scars across his face. He looked younger than me but the scars and his eyes belied a crazed kind of weariness. I put my two cameras on the table between us hoping that the gesture would placate him. In french he asked for my press pass that I didn’t have. Then asked for my passport. I had that. I put it on the table. He grabbed it and went through the pages quickly. He flipped back and forth. Each time more carefully as he read each visa and stamp. He stopped and slowly looked at my photo and name. I saw in the gloomy space behind him a crucifix. I felt then that my fate was at the end of that bullet. I had missed the crucifix when I first scanned the room. I was screwed. I counted the seconds as he flipped back through the pages again and read my name out loud. He looked at me and then read the name again. In those few quick moments from the crucifix to the stenciled tiger on the wall I knew that I was in the bunker of one of the most fundamentalist and violent of the Christian militias. And my name was Moslem. I definitely had taken a wrong turn down that Green Line. He held the passport open between his hands and moved the bullet to the side.

I tried to steady my voice as he began peppering me with questions. I leaned heavily into my ignorance. I had no choice. In french he asked me, “are you a communist?” I didn’t respond because I didn’t expect the question. I thought he would ask about my name or my nationality or my lack of a press pass or what I had been doing taking pictures of the front of his bunker. Something that made sense. “Are you a communist?”, he asked again. My mouth moved like glue and he asked a third time – this time much louder. I was stuck. Many things raced around my head. Wasn’t he going to ask me about my name? Did I look like a communist? What does a communist look like? Why would he ask me if I was a communist if my passport was American? Why would I be a communist with cameras walking the Green Line? And why a communist? Too little time to rationalize a response. The question – asked again for a fourth and fifth time ever louder and louder to the point of a scream – struck me as totally absurd. It was absurd. A communist? I held my breath and didn’t answer. He got angrier still and started to shout at me. “Are you a communist?” came at me many more times. I felt his rage. Finally I spit it out – “no, do I look like a communist?” I pictured myself wearing Lenin’s hat addressing a crowd at some train station in St. Petersburg and wondered if we shared that vision. Is that what he saw? I realized I had found my voice in my response and answered him more fully. He stopped and listened for a moment. I told him that I was talking photos for a story I wanted to write about Beirut during the cease-fire. He blasted me again with the question that I thought I had answered. He kept at it for a long time. The same question over and over again. I was shaking. His words came harder and faster like punches. He picked up the bullet and hit the table hard with his palm. I tried telling him as much about me as I could between his tirade. It was as if he didn’t want to hear me and just wanted to blast me with that question – over and over again.

I felt the boy soldier move around behind me. I bit the inside of my cheek and could taste blood. I tried to answer my scar faced interlocutor between his screams. I tried telling him about my morning walk along the Green Line while he barked at me. It was as if he had nothing else to ask me. It was as if he was looking for an answer which might legitimize his next act.

Over time I could tell that he decided by the look in my face and my answers that I had just blundered into his bunker and knew nothing about communism or what a communist looked like. Because I obviously wasn’t one. It seemed like an age before he settled down to speak to me in a sentence beyond the yelling. He went back to thumbing through my passport looking for I’m not sure what until it dawned on me that he had seen the visa for my visit to the USSR. It suddenly made sense. I thought he would focus on my name. But instead he focussed on the Soviet visa. I was grateful for that visa. It kept him focussed on what to him must have been a communist sitting across the table from him. And not the Moslem name. I relaxed a bit more.

I sat at that table for hours and hours. As his voice became less of a bark he would ask me more questions and stand up and pace around a bit and then sit down and ask them again. The cameras were square in front of him but he didn’t touch them. My passport was still there the pages folding slowly closed and the bullet now rolled on its side. I thought he would open up the cameras and take the film out to expose the rolls but he didn’t, he kept at it with the questions. I could see that he wrestled with a decision.

I was stuck in that basement bunker for a good long while. The boy soldier got a bit itchy but after a while I saw him slink off. Others still came in and out grabbing things and stacking boxes of other things. Obviously they didn’t expect the cease-fire to last long. Finally after what felt like the entire day slip by my interrogator asked if I’d have a cup of coffee. I couldn’t answer more questions. It was getting late and no one had heard from me. That started to worry me more than the questions and what might become of me. I could be disappeared too easily. I knew that and knew that he was deciding. It was way too easy.

The coffee was brought out and I sipped my cup carefully. Not knowing what to expect next. Hoping that it was over.

It was.

The coffee was placed on the table between us like white flags. Peace was at hand. I wasn’t a communist. I was just an idiot with two cameras who didn’t have a press pass who took a walk and a wrong turn. Then he started to tell me his story.

He was 19. I was three years older than him. He was the commander of the militia in that bunker. There were sixteen men in that bunker with him. He had been fighting the war in Beirut since he was 12 years old. He had lost his whole family to the violence. No father, no mother, no brothers or sister. All had been killed. He started killing when he was 12. A boy soldier like the one who stuck me in the back. He told me he loved philosophy. He told me he loved Camus and Kant. He wanted to go back to school to study. A boy soldier who had grown up in the war who wanted to study philosophy. He lived the absurdity of violence and watched his whole family die. He had been the commander of that small group of men and had seen 11 of them die in the fighting. He told me how they had died for the Virgin Mary and were in heaven. Martyrs for the cause. It wasn’t in vain. Bullets were God’s messengers and passports to another place better than this Green Line.

Our conversation went on as long as we had the coffee to drink. It was served several times. And when it was finished he told me to get on my feet. The boy soldier had suddenly reappeared and in the pit of my stomach I feared what was going to happen next. He pushed me again with the barrel of his weapon. This time my interrogator lead the way. But it was back up the stairs that he took me. Not around the back where I was certain I would go. And up into the full blast of the afternoon sun. I took each step slowly and gulped at the air and squinted in the light. I turned around and saw the boy soldier move back into the gloom of the basement giving me his middle finger as he did. My interrogator stopped me at the top of the stairs and asked me where I was off to next. I certainly didn’t have a direction in mind. All I wanted to do was to walk away as quickly as I could. He asked again where I was off to – as if he half expected me to tell him I had an appointment to have high tea with my grandmother at the St. Georges Hotel and my day with him in the bunker was just another normal day on the Green Line. It took me off guard. But everything till then had. He offered me a ride in his car. I knew he had his .45 at his side and my heart sank again. Fear comes in waves. I could feel it again in my gut. A ride to where? To the other side of the Green Line he said. I could only say yes, thinking of that .45 and the no-where that was the Green Line. I got into his car – a small bullet riddled Fiat. And in five minutes we were on the other side. He stopped under a bridge. The engine idled and I got out of the car. Hey, he said, next time I see you I will kill you. That, like all his questions, seemed to sum it all up. I walked away quickly and got back to the apartment and collapsed on my bed.

Years later I learned that the Tiger Militia and those sixteen men in that bunker and my interrogator were all executed by another Christian militia. The boy soldier with the cartoon helmet and the rest had been lined up against a wall and shot.

I never went back to the Green Line. I had very narrowly escaped being disappeared that day by the very slimmest of margins. I was saved by a stamp in my passport. Four months after the basement and many weeks of heavy fighting I left Beirut on a flight to Cyprus. The Druze shelled the runway as we took off. I watched the shells fall closer to the aircraft through my window as we taxied quickly and felt the pilot gun the engines down the runway while the passengers all screamed. I had survived my time there. The basement and many others like it afterwards. It felt like a game to me. For many it wasn’t.